Understanding Pro-choice Protests in Poland

Historical context

Reproductive rights became an important topic in the Polish public debate soon after the transition in 1989. Under communist rule, women had the right to terminate pregnancy on demand and – partly due to lack of effective contraception – became a method of regulating fertility. Within the Solidarność camp, which took a (neo)conservative turn during the mid-1980s, the anti-choice lobby grow stronger and more vocal. One of the points of the second meeting of delegates of the ‘Solidarność’ trade union was a call to ban abortion in Poland. With the catholic fundamentalists gaining more power and the liberals taking an ambivalent position, more and more restrictions on women’s reproductive rights came into effect.

The status quo was grounded in the 1993 regulations dubbed ‘the abortion compromise’ allowed abortion in four situations: when the pregnancy is a result of a crime (rape or incest), when the mother’s life or health is endangered, when the fetus shows terminal or severe genetic flaws, or due to ‘serious life hardship’. The last case was abolished by the Constitutional Court in 1997. Over the years there have been many attempts to further restrict or liberalize the law in Poland, but the ‘compromise’ stayed untouched. Nevertheless, the growing anti-choice lobby was gaining power and resources, thanks to support from the Catholic Church and international networks of religious and anti-choice organizations (Suchanow 2019).

The last years witnessed the growing popularity of a few particular anti-choice groups, with the Pro-prawo do Życia Foundation becoming one of the most famous, because of the new repertoire used for their activism. In particular they sent vans with anti-abortion (and also anti-LGBTQ) banners to the streets of Polish cities, neglecting lost court cases that forbade them such actions. These vans added to the escalation of the discourse as a counter group Kolektyw Stop Bzdurom began to block such vans and occasionally vandalized some of them in the end leading to the escalation of the anti-LGBT campaign.

Another important actor is the Ordo Iuris, an organization formed mostly by conservative lawyers, whose agenda is to fully ban the right to abortion including in vitro programs. Ordo Iuris use litigation and in recent years they have managed to secure positions in the state apparatus and among various statutory agencies. The main leader of the current wave of protests – Marta Lempart – had several court cases filed by Ordo Iuris, and in virtue of the decision of the court she was formally banned from naming the organization as ‘religious fundamentalists sponsored by Kremlin’.

The political shift started in 2015 when the conservative Law and Justice Party won the general elections with a comfortable majority in both chambers of the Parliament and placed their candidate in the president’s office. First attempt to restrict the abortion law took place soon after in 2016. The parliament decided to discuss a Citizen’s Initiative written by Kaja Godek and her organization (Życie i Rodzina Foundation), proposing a full ban on abortion in Poland. This resulted in a massive protests throughout the country staged by women that spread throughout the country creating new cross-generational alliances and activating women in small towns (https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/small-town-feminist-activism-in-poland/). With further waves of protests in 2017, 2018 and much smaller in 2019, the networks of feminist activists consolidated, crystalized and matured.

Accompanying structural changes in the wider Polish society

Despite an anti-LGBTQ campaign launched by the Law and Order Party in summer 2020, there is a growing recent support for same-sex civil partnerships. According to the IPSOS survey done in 2019 for OKO.press a clear majority (56%) is in favor of granting gays and lesbians the right to enter into civil partnerships, and as many as 41% would agree that they should have the possibility to get married (in 2017 it was 52% and 38% respectively). Polish women are much more tolerant than Polish men and same-sex partnerships are supported by 60% of them (51% of men) and same-sex marriages are supported by 47% of women and only about 1/3 of Polish men.

There is a strong and growing support for the financing the in-vitro conception procedure via the public health care system 76% (CBOS/95/2015), despite efforts of anti-choice groups to ban those procedures. Finally, there is a strong support for maintaining the previous long lasting abortion ‘compromise’. From 1992 to 2016 Poles were regularly asked about the embryopathological premise for termination of pregnancy. Each time, the majority of Poles 61% said abortion should be legal ( CBOS 71/2016).

Furthermore, Poland is on accelerated trend of secularization. According to the PEW group report, Poland is the country where religiosity is declining the fastest in the world. This can be observed along various corroborating indicators of religiosity: self-declared regular attendance to the Sunday mass: circa 40% for the age group 60+ and 26% for the age group 18-40), or attendance at religion classes taught at schools (circa 25% of high school students participate in such classes in total, in some parts of the country there are schools where religion is not taught at all due to lack of interest of pupils).

What started the protests?

Without much success in pushing through the Parliament the new laws on abortion (sent in by both pro- and anti-choice movements) a group of 119 MPs from Law and Justice, the nationalist Konfederacja with support from Kukiz’15 Party drew a petition to the Constitutional Court to declare if the most popular clause in the abortion law (the terminal or severe flaw of the fetus) is in accordance with the constitution. The 2016 protests showed that any attempt to amend or introduce a new law will be contested, therefore the submitted projects were ‘frozen’ within the legislative procedure.

In early 2020 the petition to the Constitutional Court was repeated and a new ruling by the country’s top court on Thursday October 22nd 2020 that declared termination of pregnancy of a deformed fetus is unconstitutional. This has sparked nationwide and international protests that last until today. As Anna Grzymała-Busse (2020) wrote:

One reason the PiS government went through the judiciary is because the majority of Poles support the fetal defect clause, even if abortion itself is controversial.

. The government's decision was negatively received by the public. The question "How do you assess the Constitutional Court's judgment on abortion? As many as 70.7% of respondents assessed it negatively. 13.2 percent of respondents positively assessed the verdict. 16.1% of respondents have no opinion on this issue.

What is new in the current cycle of protests?

There are several factors that make the current protests significantly different to those of 2016, 2017 and 2018. The main change is the scale of the protests. According to the head of the police force, on Wednesday, October 28th (7th day of the protests), the police registered 410 events throughout the country, frequented by approximately 430,000 people.

On-site participation in the protests suggests that both numbers can be much higher. On October 30th, 2020 a massive demonstration of over 100,000 people was organized that started from three different places in Warsaw and culminated on one of the central intersections of Warsaw (Rondo Dmowskiego) and later went to the area where Jarosław Kaczyński, the leader of Law and Justice, lives. This and the day earlier protests were less peaceful than the previous ones. On October 27th Kaczyński recorded a statement on the Law and Justice Party Facebook profile, in which he called his supporters to ‘protect the churches’, which was interpreted as a call for militant action against the protests due to rather calm reactions of the police. Attacks on protesting women were recorded in Wrocław, Poznań, and Białystok, where people were tear gassed and beaten with clubs and batons. During the big demonstration in Warsaw (on October 30th) two bigger clashes were recorded (one in the beginning) after which police detained 37 people identified as football hooligans. But the right-wingers tactics were more elaborate – small groups of around 5 right-wing militants merged with the crowd, started beating people or tear gassing people causing occasional panic in the crowd.

On November the first, the leaders of the Women's Strike announced the establishment of the Consultative Council of the Women's Strike and announced the first postulates. “The Council is to work on the voices of the protests that are taking place in Poland, to gather them and organize them” said Marta Lempart, the leader of Women’s Strike. Among the demands there were issues of abortion and women's rights, rights of the LGBT+ people, elimination of the influence of the Catholic Church on the state (introduction of a real secular state) and the removal of religion lessons from public schools, the prevention of the climate catastrophe or the elimination of the precarious job contracts. The strike also wants to address animal rights, education, and health care.

Throughout the November 2020 the protests were still taking place across Poland, but with a slightly lower frequency. Nevertheless, the police continued to repress protesting women. On November 28th, the 102nd anniversary of the granting of electoral rights to Poles, numerous demonstrations took place throughout the country. During the protest in Warsaw, the police used tear gas against the protesting women, among others against Marta Lempart, and against an opposition MP (Barbara Nowacka) just a moment later, as she showed the police officer her MP ID card.

The spread of the protest: from metropolitan cities to small towns

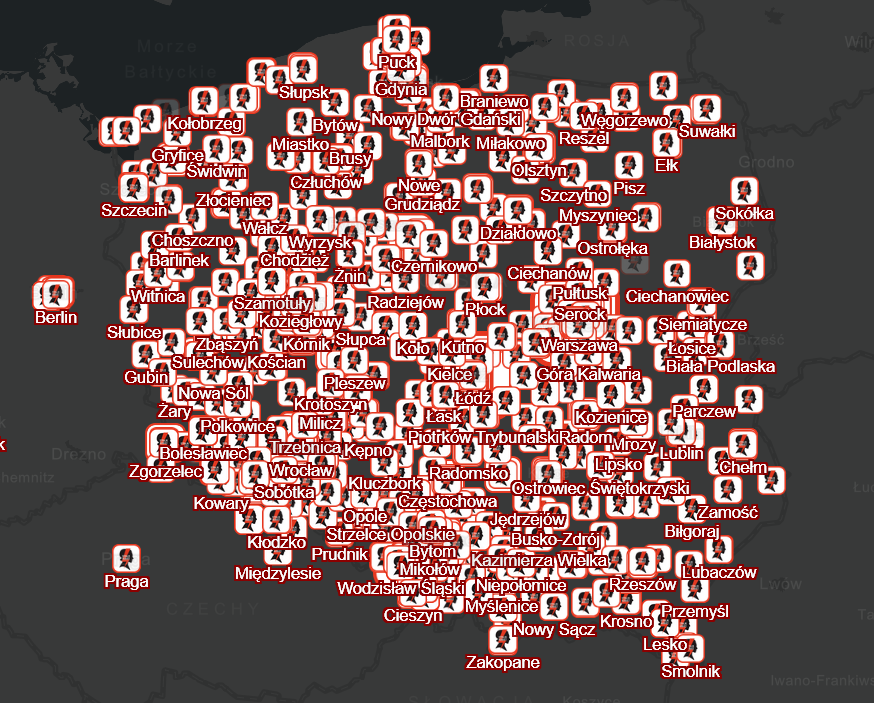

Both during the protests in 2016 and October 2020 apart from demonstrations in big cities numerous protest events were held in smaller towns in provincial Poland. A updated interactive map of the protests can be found here and reproduced below.

In 2016, the fact that the protests took place throughout the country, including in small provincial towns, whose inhabitants are the main electoral force of the Law and Order Party in government, was one of the key factors in the success of the protesters and in maintaining the so-called ‘abortion compromise’ at the time.

In most small towns, street protests have never taken place before, and the female leaders organizing them went out on the streets to shout out their demands loudly for the first time in their lives, often in the main square of the towns, located usually by the local churches. This required them to have the courage to confront the rather traditional community of their towns, where they are not - unlike in a big city - anonymous (Muszel and Piotrowski 2018). After the protests in 2016, local activists remained active and besides organizing protests, also worked for the benefit of the local communities responding to different needs, specific to the local community of small towns.

In 2018, many of them tried their luck in local government elections and became councilors in their towns, and in 2019, several of the small-town activists also became deputies in the Parliament. These four years of activity have given them the opportunity to acquire the skills, qualifications and social contacts that have enabled them to organize their protests in small towns quickly and effectively in October 2020. The scale of protests in small towns in 2020 turned out to be even greater than 2016, for example, on just one day (26 October, Monday), according to data from the official website of the National Women's Strike, the protests took place in 201 towns, including those with only a few thousand inhabitants (e.g. Lesko, Zelów) or even just over one thousand (e.g. Sarnaki). As in big cities, although to a slightly lesser extent, in small towns also men are joining the protesting women. The fact that the protests cover the whole country, including small towns, makes the voice of the protest stronger, more coherent and more representative of all Polish women and men.

Protesting… in pandemic times

When the petition to the Constitutional Court was repeated by a group of MPs in the spring of 2020. During the lockdown introduced in Poland, spontaneous pickets were organized. In order to avoid fines for organizing ‘public gatherings’, the official justification was queuing in front of shops in city centers, but the scale of these initiatives was small. Currently:

Because of current restrictions on public gatherings due to the pandemic, some of the abortion protesters have demonstrated by using their cars to block traffic and beep their horns.

Yesterday [October 25th], as several hundred cars took part in such a protest in Kraków, they were joined by some taxi drivers, who displayed Women’s Strike logos in their windows and flew white-and-red Polish flags. Taxis also took part in a similar protest in Warsaw, reports Radio Zet” (Wilczek 2020). Motorized protests became a constant element of the women’s protests that are organized daily and cavalcades of cars and motorcycles drive around the cities, using their horns, and blocking traffic. Occasionally tram and bus drivers stop their vehicles to join the strikes.

Witnessing a generational turnover

When attending the 2020 protests, one of the things is also noticeable. It’s the young age of the crowds, people up to their early twenties are the vast majority of the protesting crowd. Perhaps it is the reason for the radicalism of the claims and slogans. As one of the organizers of the protest said:

Young people are uncompromising, they do not want to get along. They have grown up with a sense of freedom and now someone wants to take it away from them.

Another of the organizers of the protests we have been talking with, noted about the differences between the women’ protests in 2016 and in 2020:

Now there is a completely different energy. It’s wonderful. They are young people and they have no fear of taking to the streets and fighting for their rights. They are looking wider. They are afraid that they will be deprived of more freedoms, more rights, more spaces, that this is a dictatorship that will impose everything on them.

(Organizer of the protest in Sochaczew, a town with about 35,000 inhabitants, interviewed by authors). What is happening on the streets of Poland in 2020 shows what has happened to the generation that is becoming adults at the moment. A large number of especially Polish young men are actively supporting women on the streets chanting slogans in support of women and joining in other forms of the protest. The support (coming even from conservative environments, such as football fans and hooligans) for women’s struggles over reproductive rights suggests that the changes in the understanding of gender roles in Poland are much bigger than previously expected.

One characteristic part of this phenomenon is the narrative of rejection of a group called ‘dziaders’ (roughly translated as ‘the old folk’) – politicians, opinion makers and former dissidents who criticized the ‘vulgar’ narrative and slogans of the protests and the repertoires of protests. The mostly young people participating and organizing the women’s strikes and protests, among others, coined the term and began to refuse to listen to or discuss with the ‘dziaders’. In Poznań the local chapter of Committee of Defense of Democracy [Komited Obrony Demokracji], a group often associated with people 50+ and connected to the liberal circles, was ejected from the committee organizing the protests under the argument of trying to take over the protests, suggesting an alliance with football hooligans (who went through the city chanting ‘death to antifa’), and mansplaining.

This text is based on research conducted within a project Feminist activism in small towns/Feministischer Aktivismus in Kleinstadten funded by the Polish-German Science Foundation Deutsch-Polnische Wissenschaftsstiftung.

RERENCES

Grzymała-Busse, Anna (2020) Poland is a Catholic country. So why are mass protests targeting churches? The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/10/28/poland-is-catholic-country-so-why-are-mass-protests-targeting-churches/?fbclid=IwAR1qle0O2ZjyO8mFxTAbsuFB0gLfLfvfEqXYpAFjYJrv1xk0Qf9Iauxfzfc

Kubisa, Julia, & Rakowska, Katarzyna (2018). Was it a strike? Notes on the Polish Women’s Strike and the Strike of Parents of Persons with Disabilities. Praktyka Teoretyczna, 30(4), 15-50.

Majewska, Ewa (2020) Poland Is in Revolt Against Its New Abortion Ban, Jacobin Magazine, https://jacobinmag.com/2020/10/poland-abortion-law-protest-general-strike-womens-rights?fbclid=IwAR0TlpBqwQazD8wbhDvAHwqOptNgyGc_YI_KikIG9sIy_JQPX0lPg_M6Mgw

Muszel, Magdalena, & Grzegorz, Piotrowski (2018). Rocking the small-town boat: Black Protest activists in small and provincial Polish cities. Praktyka Teoretyczna, 30(4), 102-128. https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/prt/article/view/19010/18735

Suchanow, Klementyna (2020) To jest Wojna, Wydawnictwo Agora

Wilczek, Maria (2020) Farmers, taxi drivers and miners show support for abortion protests in Poland, Notes From Poland, https://notesfrompoland.com/2020/10/26/farmers-taxi-drivers-and-miners-show-support-for-abortion-protests-in-poland/?fbclid=IwAR00Fd5EOx19-N-TeOQfYb02gYvbNQJZFdT9FChcfcJhBn7KD-W4DXtkRCQ