The 'Trojan Horse' Scandal and the Problem of Equalities in Britain Today

Written by Walaa Al Husban

In this post, Doctoral Student Walaa Al Husban discusses the continued importance of the ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal after a panel discussion hosted by CERS at the University of Leeds.

In early 2014, 21 schools in Birmingham city were accused of a supposed Islamic conspiracy, known later as the ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal, after an anonymised letter was sent to the Birmingham city council. The letter, allegedly written by a Muslim teacher, purported to provide evidence of an extremist plot to take over schools and run them according to radical Islamic principles. Despite finding no evidence of extremism or radicalisation, many Muslim teachers and governors were suspended and special measures were implemented on the schools due of allegations of ‘undue religious influence’. Ultimately, however, the allegations were dropped and the case collapsed in May 2017.

The scandal is part of a wider structure of Islamophobic narratives, signifying the international discriminatory and racist polices and legislations against Muslims and Islam. It symbolises the continuity of certain radical connotations; Islam as a ‘threat’, Muslims as ‘extremist’. To address this issue at length, the Centre for Ethnicity and Racism Studies (CERS), University of Leeds, held an event on 1st of May 2019 at the School of Sociology and Social Policy entitled, 'The Trojan Horse Scandal and the Problem of Equalities in Britain Today'. The panel was chaired by Dr Ipek Demir and included: Professor Jeremy Hingham, University of Leeds; Professor John Holmwood, University of Nottingham; Dr Shamim Miah, University of Huddersfield; and Professor S. Sayyid, University of Leeds. The event examined the scandal from a broad range of perspectives, engaging with debates on equalities, liberalism, and Britishness. It also provided an opportunity to discuss and generate a dialogue about the significance of the ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal and the duty placed on schools after the scandal to promote Fundamental British Values (FBV) in the promotion of democracy. Speakers analysed how both are reproducing narratives of racial discrimination and inequalities in a context that is informed by minoritising communities, problematising specific religious values, and essentialising the signification of social, religious, and cultural identities.

‘Trojan Horse’ and Fundamental British Values

In 2014, the UK’s Department of Education published a detailed document on the obligation of schools to recognise and promote FBV, including: ‘democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect and tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs’.[1] These values were associated with schools’ requirement of providing a balanced curriculum through promoting (SMSC) – spiritual, moral, cultural, mental, and physical development.[2]

The promotion of SMSC has long been considered an obligation of British schools and was associated with the duty to promote ‘community cohesion’. Interestingly, in 2014, after the scandal broke, the Department of Education declared that SMSC-linked purposes could be maintained through promoting FBV, and any ‘Attempts to promote systems that undermine fundamental British values would be completely at odds with schools’ duty to provide SMSC’.

Professor Holmwood explained how the ‘Trojan Horse’ has shaped debates on community cohesion within the national curriculum: The criteria and strands which once were associated with the duty to promote community cohesion have since been linked and (re)incorporated with the duty to promote FBV.

Through such a new framing, British values became another medium used to ideologically theorise the values of certain cultural differences, while disregarding others. In a way, FBV is now being used to identify and reclassify the subordinate nationalities and ethnically marked minorities. Advancing the idea that there is only one way to be British, which is to abandon the values of your culture in favour of supposedly British values. In the case of the ‘Trojan Horse,’ the less Muslim you are, the more British you became.

However, as Professor Holmwood pointed out throughout his presentation, what seems to be of most concern regarding FBV is how, after the scandal, it has been imposed as a duty to prevent radicalisation and protect children from being exposed to extremism,[3] because imposing FBV in this way implies that the British are immune toward any form of radicalisation and only those whose values are perceived as not or opposed to British values are potential security threats. Thus, the securitization of FBV in the awake of ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal paves the way to reinforce the existing hegemonic narrative regarding the attribution of Muslims’ cultural background as opposing FBV and therefore suspect of radical and extremist behavior.

The questions that one should ask are: First, how can Muslim teachers and students access an inclusive and diverse education curriculum, while their religious values have been conceived of as a potential risk? Second, if in Professor Holmwood’s words the religious values of Muslims have been ‘left outside of the school gates,’ how can Religious Education, a core part of the British curriculum, be maintained when the religious values of British Muslims are being erased?

If anything, these questions indicate the government's contrary stipulation of Religious Education. This is particularly evident, as Professor Higham clarified, when discussing the Education Act of 1944 and Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education (SACRE). The central purpose of both is to promote community cohesion through bringing together the different religious dimensions of the community, including Islamic values.

From this perspective, Professor Holmwood focused on the debate around the actual Britishness of the so-called FBV. He argued that FBV ought to be considered as part of the liberal discourse of what is ‘right,’ instead of as British values. For example, the ‘No Outsiders’ curriculum, which seeks to promote LGBT rights, was part of the schools’ duty to teach FBV. However, as Professor Holmwood clarified, there is a difference between rights and values. In this case, the LGBT community has the right not to be discriminated against, but not the right to impose its values on those parents and communities with different faith-based views. Ultimately, Professor Holmwood concluded, FBV is a representation of the liberal secular agenda. Specifically, its positions toward restricting Article 9 of the Human Rights Act, which ‘protects the right to freedom of thought, belief and religion,’ including ‘the respect for the liberty of parents to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions’.

The Racial Grammar Behind ‘Trojan Horse’ Investigation

The 2014 investigation of the scandal, which was conducted by Ofsted (the official regulator for education in Britain), concluded that five of the 21 schools in Birmingham should be put into 'special measures' because of potential risks of ‘extremism’ and ‘radicalisation’. Nevertheless, as Dr Miah clarified, all the reports could not identify a single child that had been radicalised, nor any evidence of extremism or a conspiracy to promote an anti-British agenda. This contradiction reveals how the Ofsted investigation was also scandalous, portraying Muslim teachers and children in these schools and elsewhere as violent radicals.

Dr Miah discussed in detail the flawed impartiality of Ofsted. He argued that the official narrative of the 21 inspections demonstrates a racialised politics, evident through the following. First, the way that the Ofsted inspection team had altered the base of their investigation away from the regular, systematic framework of the Ofsted Inspection Handbook to the government's Prevent Extremism Strategy, specifically section 10 of the Prevent Strategy (2011). Second, the selection of the main criteria for inspecting the 21 Birmingham schools were not based purely on evidence, meaning the ‘Trojan Horse’ letter, but rather on schools with a Muslim majority of students and teachers.

According to Dr Miah, approaching the ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal with such a racialised grammar entails a deliberate alienation of British Muslims, reflecting the political nature of Britain’s contemporary educational discourse. This discourse is mediated through a radicalised politics and still influenced by the historical narratives of the racialised construction of ‘the other’.

‘Trojan Horse’ through the Lens of Liberalism and Nationalism

Professor S. Sayyid described the ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal as a floating signifier that ought to be analysed through situating it within the overlapping projects of a national liberalism. That is a form of liberalism that priviliges nationalism as a mode of political expression and is complicit with imperialism, colonialism, and racism.

According to Professor Sayyid, liberalism is not what it purports to be, as it is neither neutral nor universal. One result is that liberal educational policies in Britain, especially after the scandal, have contributed to the violation of several human rights, unduly presenting Muslim communities as suspects of violence and radical extremism. Nationalism as an ideology is also intertwined with the hegemonic liberal discourse, which according to Professor Sayyid can be argued through the way that both create specific ethnic foundations of the ‘national majority’ versus those who are constructed as ‘minorities’.

One side of this argument, I would say, is the question of the authority that is presumed by setting out such categorical identities: the ‘national majority,’ which has been conceived of as the authentic dominant model for the formation of any British public norms (education, religion, etc.), is echoing the historical narratives of imperialism, colonialism, and racism. Meanwhile, the ethnic minorities are constituted as irrelevant others, who need to be grouped to protect the existence and the hegemonic power of the ‘national majority’.

Conclusion

The ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal reveals the hegemonic politics of discrimination, racism and inequality that British Muslim communities are encountering in an assumed multiculturalism Britain, unveiling the normalised radicalisation narrative regarding the construction of Muslim identities.

In the wake of this intellectual and inspiring dialogue, broader concerns have been raised which are about the lack of a proper response by human right activists, academics and politicians to uncover and challenge the impact of the ‘Trojan Horse’ scandal. Including: the negative hegemonic representation of Muslim communities, the misrecognising consequences of the current radicalisation and extremism policies on the schools’ educations system, students, and society. Equally important, the contemporary role of British values, especially when discussing the importance of the community cohesion, a sense of citizenship, and the equal integration of all British.

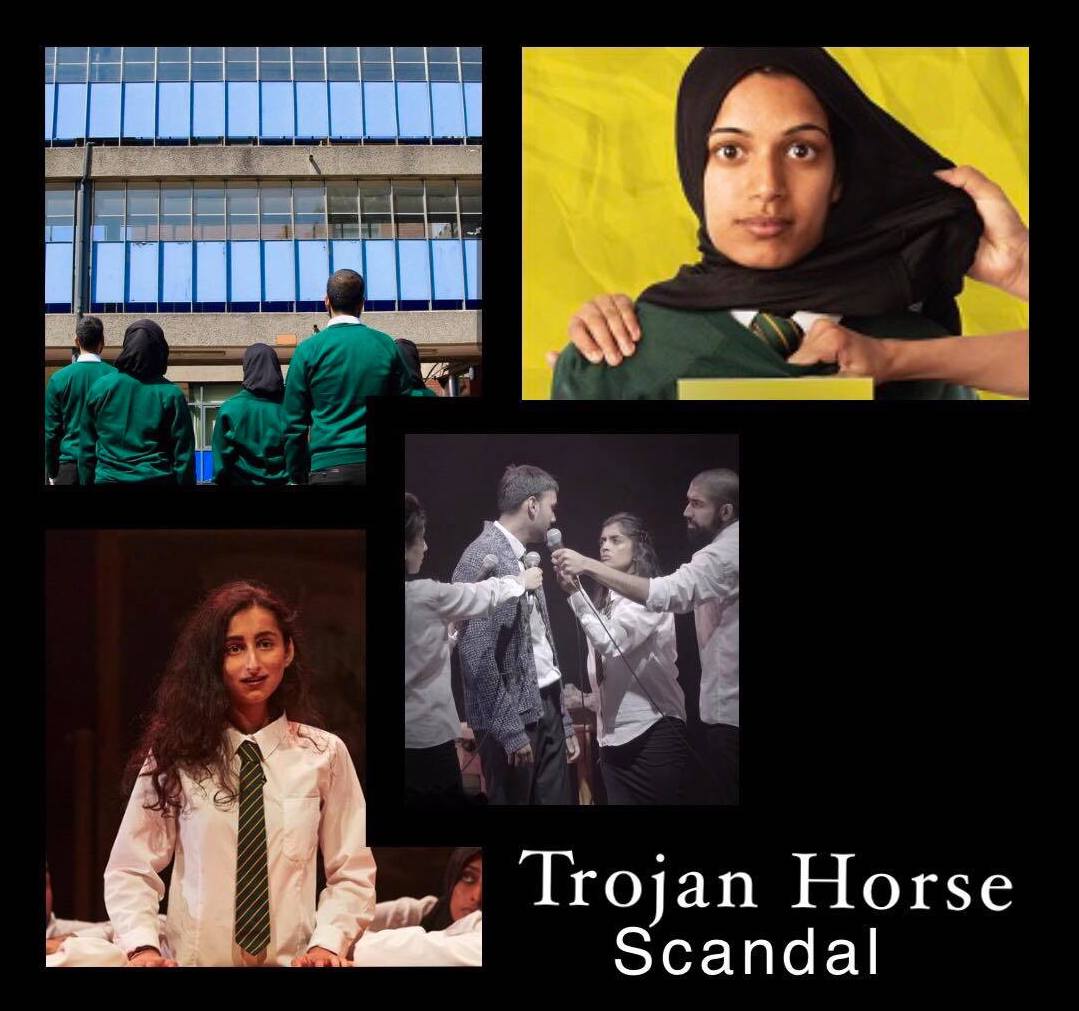

Book your agenda: Trojan Horse play coming to Leeds.

'Why should I continue to be tolerant? When the world has been so intolerant of me.' Based on real-life testimonies, 'Trojan Horse' is a documentary play that provides an insight into the ethical impact of the scandal on the life of teachers, students and governors who were directly involved in the 2014 extremism allegation. The winner of Amnesty International Freedom of Expression & Fringe First awards, Trojan Horse, is coming to Leeds Playhouse on Thu 3rd Oct 2019 – Sat 5th Oct 2019, 7:45pm.

For more information on Trojan Horse tour please check LUNG webpage.

[1] Promoting fundamental British values as part of SMSC in schools. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/380595/SMSC_Guidance_Maintained_Schools.pdf

[2] The SMSC was first mentioned in 1944 acts under the 'Statutory System of Education,' Part II section. The term becomes more recognisable in the 1988 Education Act, under the 'cultural development' section, which was then endorsed in section 78 of the Education Act 2002.

[3] According to the Department for Education, 'Schools and childcare providers can also build pupils' resilience to radicalisation by promoting fundamental British values and enabling them to challenge extremist.' Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/439598/prevent-duty-departmental-advice-v6.pdf