Songs, Chants and Poems of the Sudanese Revolution

In this post, Dr. James Dickens, Professor of Arab in the Department of Arabic, Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies (AIMES) at the University of Leeds, explores the cultural evolution of the ongoing revolutionary movement in Sudan.

In December 2018, beginning in the northern Sudanese city of Atbara, protests broke out against the country’s military-Islamist regime, led by President, and former Colonel, Omar Al-Bashir and backed by the Islamist organisation, the Muslim Brotherhood. The immediate trigger was the regime’s decision to triple the price of bread. However, behind this lay decades of anger at an astonishingly brutal government which, since coming to power in a military coup in 1989, had engaged in unprecedented political repression, and civil war.

From the outset, the regime had attempted to Arabise Sudan’s non-Arab population – a majority before the independence of South Sudan in 2011), force non-Muslims to adopt Islam, and impose the Muslim Brotherhood’s version of Islam on Sudanese Muslims. The regime crushed its political opponents, holding many in secret ‘ghost houses’ (buyūt ašbāḥ), where they were tortured and killed.

The regime pursued civil wars across the ‘peripheral’ regions of the country. In South Sudan, it killed up to 2,000,000 people in an unsuccessful bid to prevent the South breaking away from the rest of the country. In Darfur in western Sudan it amplified tensions over land, particularly between Arab and non-Arab tribes, killing up to 400,000 people. In other regions such as the Nuba Mountains (Kordofan) and the Ingessana Mountains (Blue Nile) the regime also engaged in mass slaughter.

These wars, which consumed up to 75% of the national budget, were funded by revenues from oil, discovered in the 1980s. Oil also helped fuel massive corruption; in 2011 Transparency International ranked Sudan 177th out of 183 countries on its Corruptions Perceptions Index. Since the vast majority of the oil was in South Sudan, these revenues virtually disappeared following South Sudan’s independence. As a result, the country was gripped by a series of economic crises and the great majority of Sudan’s population became impoverished, even outside the war zones.

The protests which began in Atbara rapidly spread to other cities in Sudan, including the capital Khartoum, and the focus shifted to forcing the regime from power. In April 19, the protestors were able to depose Omar Al-Bashir, and almost immediately afterwards the army’s designated successor, Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf. By Sept. 2019, the protests were so successful that the military agreed to transfer executive power to a mixed military-civilian collective head of state, as a prelude to national elections and a fully civilian government in 2022. In Oct. 2020, the Sudanese government began talks with the International Criminal Court (ICC) to hand over Omar Al-Bashir, to stand trial for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity – one of the key demands of the protestors.

From the outset the revolutionaries demanded a madani (‘civilian’ – also ‘civil’, i.e. secular-type) government, rejecting the Islamism of the Muslim Brotherhood, which is widely blamed for collaboration in the regime’s human rights abuses and financial corruption. The civil(ian), anti-fundamentalist nature of the Sudanese revolution sets it apart from the 2011 Arab uprisings with their strong Islamist component. This arguably presages further democratic, secular-oriented uprisings across the Arab world, as young Arabs reject both their corrupt regimes and the hitherto dominant but intolerant Islamist opposition to these regimes.

The Sudanese revolutionaries insist on the multi-ethnic, multi-religious nature of Sudan, contradicting the regime’s policy of Islamisation and Arabisation. According to official, though not necessarily accurate, figures, Sudan is c. 70% Arab and 30% non-Arab. Shorn of South Sudan, where the majority are Christian and/or traditional religionists, Sudan is almost entirely Muslim. This makes the insistence on the multi-religious nature of the country even more striking. Unlike in other Arab uprisings, women have played a prominent role.

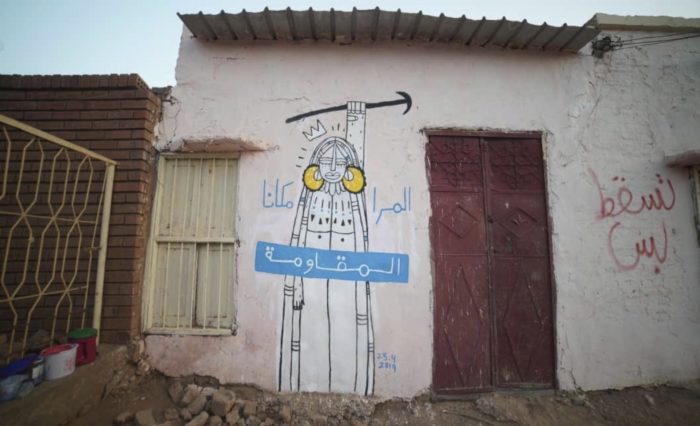

“A woman’s place is in the resistance”

Since 2019, I have been working on a project to document the songs, chants and poems of the Sudanese revolution. My goal is to produce a Sudan Revolution Oral Archive as a digital depository, using material I have collected on YouTube and internet sites, plus further material which I will collect in Sudan itself, in order to preserve the songs, poems, chants and talks of the Sudanese revolution for future reference and research. I intend to spend the academic year 2021-2022 in Sudan attached to the Centre d’études et de documentation économiques, juridiques et sociales) (CEDEJ), which has begun own broader Sudan Revolution Archive from Jan. 2021: https://cedejsudan.hypotheses.org/. Since the material I am collecting is only stored on the internet, it is currently highly impermanent. It provides, however, an unparalleled record of a peaceful revolution against a brutal regime, representing part of an artistic outpouring – poetry, songs, chants, paintings, murals, pavement art, graffiti, clothes, body paint – which accompanied and propelled that revolution. This material is a source of immense pride to Sudanese, who see it as heralding the rebirth of their country, and constitutes an informal popular record of the revolution. Its preservation is considered essential by Sudanese I have spoken to, e.g. at the Society for the Study of the Sudan UK Annual Symposium, 2019: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GY6_8c8FL0Y. It is largely in Sudanese (colloquial) Arabic, with some Standard Arabic, and is extremely broad. Song styles range from traditional solo and call-and-response, to Sudanese ‘Afro-pop’, Western- and Arab-influenced forms, reggae and rap; poetry ranges from traditional to innovative. Chants are often witty and incisive; many inspired and were incorporated into songs and poems.

I have so far downloaded 116 YouTube items (videos) of revolutionary songs, poems, chants and talks. I identified these during 2019 (downloading most in 2020), as the revolution was taking place, on the basis of (i) my assessment of their relevance to the revolution; (ii) the popularity of the item (view count); (iii) the intrinsic interest of the content; (iv) the relatability of the item to other items (e.g. of a chant to a subsequent song incorporating elements of that chant). To my knowledge, this corpus is unique. Many of the items have accompanying words on the videos themselves – or from internet sites. I also intend to collect further material in Sudan, partly from recordings I will make from well-known revolutionary artists. For each item, I will produce 1. An Arabic-script transcription; 2. A Latin-script transliteration; 3. An English translation; 4. A cultural and linguistic commentary. For the digital depository, I will have both Arabic-script and Latin-script forms. The former is essential for native speakers of Sudanese Arabic, who are a major intended user of the archive, while the latter is standard for Western academics (Arabic dialectologists, etc.).

The cultural element of the commentary will firstly place the item (song, poem, chant, talk) in its specific context within the unfolding revolution. It will then identify the genre, and in the case of songs, poems and chants, its salient prosodic/rhythmic and, where appropriate, melodic features. The linguistic analysis will provide an account of key linguistic features (e.g. lexis, emphatic forms), chosen for their significance in the text and their interest to the general as well as academic reader.

When in Sudan, I intend to consult with qualified Sudanese, e.g. revolutionaries who are part of the Sudanese Professionals Association, which was central to the revolution’s organisation and ultimate success. This will allow me to check that the items included have the significance I believe them to have (and where I become convinced they do not, discard them), and identify further items to work on, having completed work on my initial corpus. In addition to my current entirely internet-based material, I will consult with qualified Sudanese revolutionaries to identify significant oral material not available on the internet, e.g. songs by well-known artists. I intend to make the archive fully bilingual in Arabic as well as English, allowing maximum usability for Sudanese as well as other native Arabic speakers.