Feeding the Nation: The lives of seasonal migrant workers

Written by Bethany Robertson (University of Leeds) Roxana Barbulescu (university of Leeds) and Carlos Vargas Silva (COMPAS, University of Oxford)

Do we care for the people who care for our food? Read about a project that explores the experiences of seasonal migrant farmworkers.

Why do seasonal workers’ voices matter?

Food security is at the forefront of our minds since Covid, Brexit and the ongoing war in Ukraine. These disruptions have highlighted farming as essential work to help feed the nation. What is lesser known is the community of migrants who arrive in the UK on a seasonal basis to plant, pick and pack fresh fruits and vegetables. The number of migrant workers in UK horticulture was estimated at 75,000 in 2018 with 90% being from overseas. Large numbers have come from Ukraine in recent years.

As part of a recent UKRI project Feeding for Nation, which brings together social scientists from the University of Leeds and COMPAS at the University of Oxford, we have developed an interactive dashboard to show the historical and recent trends in seasonal migration in UK farming. We have seen from the MERL’s Changing Perspectives in the Countryside that many voices have gone unheard under the guise of rural spaces being seen as homogenous. Our new exhibition, and the research project it is based on, make labour migration in the countryside visible.

Beyond the idea of a static rural community, seasonal migrant farmworkers come and go each year, contributing to our food system and rural economies. They are hard to reach, yet economically important as farmers depend on seasonal labour from overseas to process crops and fulfil retail orders. In turn, this keeps local people employed elsewhere in the business and ensures that farms can thrive for future generations. Following Brexit, farms cannot recruit as easily as they did under the Freedom of Movement. Alternatives to migrant labour in farming have been identified, but migrants continue to make up the fabric of seasonal rhythms in the countryside due to the difficulties of recruiting workers from the UK for temporary work in rural locations and automated technology being early in development. Labour shortages have drawn attention to working conditions and we spoke to farmers and seasonal farmworkers to find out about their experiences of post-Brexit immigration, work priorities and mobilities.

Voices of seasonal workers from the research

Seasonal migrant workers often aim to return here annually to support their families. The majority support children in further education in their home countries, saving during the six months they work in seasonal agriculture for advance payments on their homes, buying a car or starting a business. For the younger workers, financing their education is a personal goal and the older seasonal workers who work farming at home often also use the savings to expand their farms. Seasonal migrant workers can arrive by applying for a visa that bears the name ‘Seasonal worker visa’ or can be domiciliated migrants who tend to be from the EU countries and have settled or pre-settled status. With different associated rights, their experiences vary significantly, affecting how long they can stay and if they can return the following year for the same work.

Migrant workers: The raspberry planter

Migrant farmworkers tend to live in static caravans for the duration of the season. Strong bonds develop between the occupiers who cook, do groceries together and often also work on the same team in the field. Workers know little or no English, particularly those who come for the first time, so finding friends to share the experience with or lean on in difficult times is vital for pulling through the season. There are also negative experiences, with workers reporting being maltreated or shouted at by field supervisors and row inspectors. They also often speak with pride in their work. What is most difficult however is being away from families and friends and feeling isolated because of the remote location of the farms. Internet and phones are a connection to their loved ones and their known world, as well as their main source of entertainment. Whilst their presence is transient, with this exhibition we aim to put the spotlight on their lives as part of rural communities.

Whilst the majority of seasonal workers arrive in May or June for harvest, a smaller number arrive in the UK all year round as they contribute to a variety of jobs on the farm. In the winter and early spring months, migrant workers care for raspberry canes, planting, keeping the canes in good condition, replacing frames, pruning the canes and protecting them from birds in rain, wind or hail. Raspberries are fragile to harvest and require individual handpicking and continued delicate care in packing and transporting as they make their way to our pastry chefs, ice cream makers and the tables of thousands of families across Britain. Why not rediscover British raspberries and explore new things to do with them?

Explore a day in their life in the online exhibition

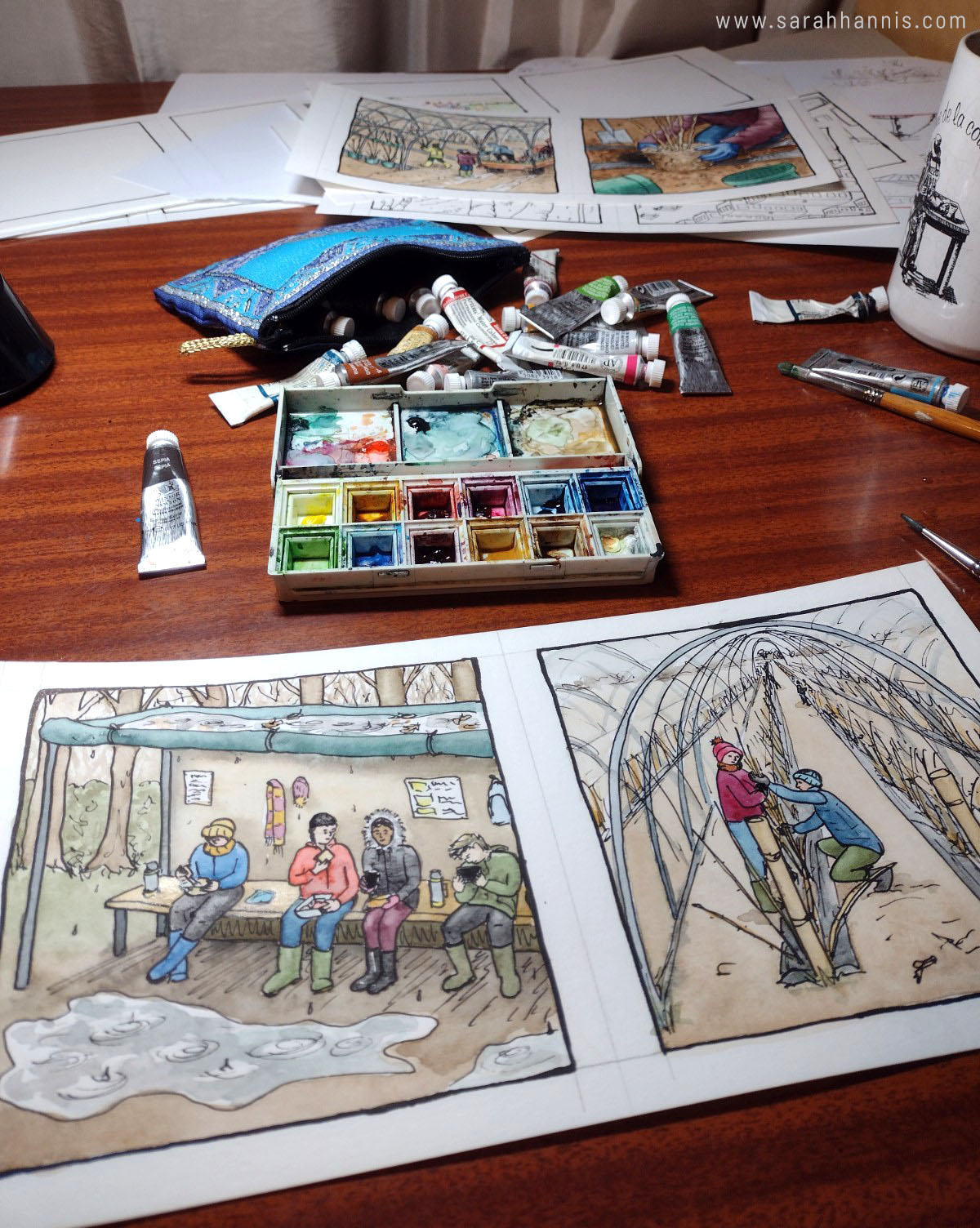

The research team have collaborated with the MERL and artist Sarah Hannis to produce a series of illustrations based on encounters with participants in the research and photographs taken by migrant workers themselves. Please visit and share the exhibition which takes you through a day in the life of migrants who are living in the UK for seasonal farm work.

To find out more about the Feeding the Nation project, take a look at the website.