Falling through the cracks? PhDs, inequalities and Covid 19

Image by Clara Hoke - Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35111137

In this post, Leed's Sociology and Social Policy PhD student Karen Tatham suggests that the inequalities in the PhD process will be further entrenched by Covid 19.

PhD students are at risk of falling through the cracks in the Covid 19 pandemic; they are facing a range of issues from suspended research to caring responsibilities, and health risks from inadequate working conditions. These factors are layering on top of existing inequalities in the PhD experience, from access to funding and wider opportunities. There is a normative framing of privilege in studying at a doctoral level, meaning that the difficulties facing PhD students with the lowest financial resources are often invisible in the wider university. There is a risk of drop-out. The ability to mitigate suspended or extended study periods and build future employability in highly competitive jobs markets is reduced for lower-income students. Financial support to date has only applied to those scholarship students in their third year, showing how systemic inequality is reproduced for individuals through the multi-layering of micro-inequities. Pre-Covid, only 10-15% of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences PhD students achieved an academic research career. If you wanted to be a Professor... well only 0.5% of PhDs make this, so maybe you need a back-up plan? Furthermore, the Covid-19 impact on Higher Education now risks creating a lost generation of researchers, which will further affect those with the lowest financial resources and their ability to ride out the storm.

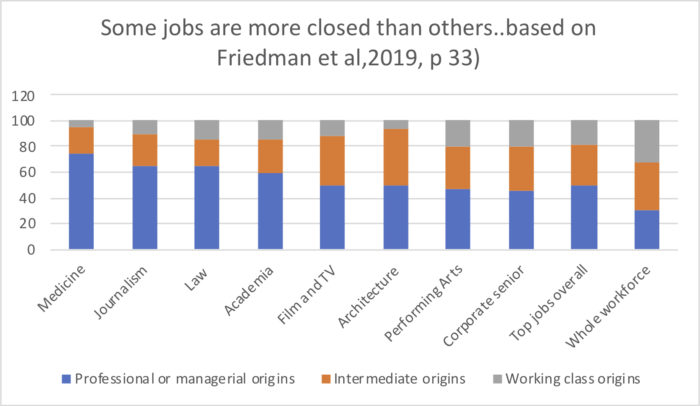

Inequalities seen by PhD researchers mirror those observed in many elite organisations in recruitment and progression. Friedman and Laurison (2019:7) suggest that processes of ‘getting in, fitting in and getting on’ entrench highly classed patterns of economic and social privilege in elite institutions such as medicine, law, journalism and academia. Ingram and Allen (2019) describe these processes as a cultural sorting through Bourdieusian concepts of social magic and institutional habitus, along with the role of unconscious bias in the right to inhabit space. In these processes, notions of cultural fit, access to social networks, and perceptions of ‘othering’ intersect to invisibly exclude marginalised groups from recruitment and progression opportunities. Friedman and Laurison’s study concentrates on class, but demonstrates that similar exclusions are occurring by race, disability and gender.

Source Labour Force Survey in ‘The Class Ceiling’ (2019)

In academia, UKRI is facing charges that its gold standard of PhD scholarship is biased against marginalised groups, with little external accountability as to how decisions are made and who is and isn’t successful. Here, value is placed on publications and research assistant experience, which for UKRI act as signals of academic talent, both of which favour the young, mobile, and affluent, who can afford to take on low paying research assistant jobs which build these opportunities. This is not just a ‘getting in’ barrier, as these scholarships then provide further exclusionary opportunities through publication and research placements with leading policymakers. These structural inequalities create invisible barriers for other students and contribute to under-representation in academic workforces further up the academic pipeline.

HEPI reports on the difficulties from the position of PhD students as an intersection between students and staff. This creates notions of PhD students as ‘others’ who are invisible in many policy arenas. The Social Sciences forms one of the most diverse groups of doctoral students and could provide insight into the inequalities experienced in the PhD process for marginalised groups, since there are not many ‘jobs’ where the financial resources or opportunities available to individuals on common pathways are so disparate. The standard UK £15k stipend, although low for the hours worked, looks positively affluent when compared to the UK Doctoral Loan which leaves £4.5-£5k per year once fees are paid. Immersive scholarship requires significant financial resources to allow students to dive deeply into the literature and produce quality writing. There is institutional pressure for PhD students to complete their studies within three years, and academic success is predicated on publishing and disseminating your research via conferences and networking. External paid work beyond 10 hours is discouraged because of the impact on the quality of academic study. But this raises significant questions about the understanding of universities as to the realities of the financial circumstances of their PhD students and representative institutions. Are universities saying that only the privileged can study full time via government loans, given there are few significant efforts to level up opportunities? Even funded students report financial pressures, particularly if they are also carers, or have few family resources to draw on. Covid 19 adds to these existing pressures through increasing the level of financial resources required for extended study due to its related societal disruptions, and the future competitive nature of the UK post-Covid 19 job market.

The reasons for why inequalities are not being addressed by academics are complex. Bottero (2019) suggests that theories of power, powerless and practical constraint can begin to explain these patterns. Theories of symbolic legitimation suggest that funding inequalities are the result of natural talent, or that academics accept institutional or societal norms which they deem beyond their control. In theories of powerlessness and practical constraint, however, academics are often as constrained by the system as the students, and the professional risks of challenging practices are too great. This means, even when individuals are sceptical of the values and beliefs in institutional systems, they will still conform to them. Easier to explain is the unequal power position of the student, who may perceive that speaking out about the system of unfair funding risks inviting ridicule as to their ability; or the student may feel powerless to challenge the authority of the system which manages their progress and awards them their qualification.

No-one has bundles of cash to give to students, but a university has many resources beyond grants that would actively begin to level up opportunities, especially in the light of Covid 19. A good place to start would be to mirror the UKRI wider opportunities on offer. This should be a focus on publication, with appropriate student protections, and access to wider research placements, which would need embedding in the doctoral standards and supervisory responsibilities. Three-year PhD research periods are an arbitrary measure, and greater recognition is needed of models that would allow students to earn alongside full-time study. At the same time, valuing the expertise of non-academic careers more, and honesty about the low numbers who succeed in academia, would support all PhD students and has importance given the Higher Education cuts to come. Evidence shows a premium for post-doctoral earnings. Recognition of the barriers that low-income students face might mean a more equitable chance for all PhD students to achieve this.

The ladder of life is full of splinters by Mykl Roventine at https://www.flickr.com/photos/64419960@N00/4143699557.

Works cited

Bottero, W. 2019. A Sense of Inequality. Rowman & Littlefield International.

Cornell, B. 2020 PhD life: The UK Student Experience. HEPI

Friedman, S. and Laurison, D. 2019. 'The Class Ceiling: Why it pays to be privileged,' Social Forces.

Ingram, N. and Allen, K., 2019. '"Talent-spotting" or "social magic?" Inequality, cultural sorting and constructions of the ideal graduate in elite professions,' The Sociological Review, 67(3), pp.723-740.

.