Rethinking Human Rights

Written by Johanna Loock

THE West has claimed ownership of human rights and used them to establish and cement Europe’s superiority over non-Europe. A panel on ‘Decolonising Human Rights’, hosted by the Leeds Human Rights Journal and the Centre for Ethnicity and Racism Studies, has proposed alternatives to universalist understandings of human rights. In this post, Johanna Loock reflects on the panel discussion.

Contemporary examples of human rights violations or denials abound in Europe and other places. Refugees and asylum seekers are heavily impacted by this development. In my own research, I am concerned with how refugees who are denied basic human rights, on entering several European countries are obligated to commit to and adopt civil rights and liberal values that are linked to human rights – the premise being that these are not part of their original canon of values. This paradoxical approach to human rights in relation to refugees allows the West to construct a supposed deficiency of refugees and conversely enables the hegemonic power to reaffirm Western national identity and supremacy.

The investigation of inconsistencies around human rights and the supposed universality of their application (especially regarding refugees and stateless people), has a long history. In the aftermath of World War II, Hannah Arendt revealed the paradox that access to human rights, which are supposed to secure a minimum of rights for the disenfranchised, depends on holding citizenship rights. This implies that the permanent presence of minorities and stateless people on a given national territory poses a challenge to the nation-state based on “the old trinity of state-people-territory”.[1] Arendt diagnosed “the Decline of the Nation-State and the End of the Rights of Man”[2], an assertion that Giorgio Agamben stated should be taken seriously. Since it “indissolubly” links the fate of the modern nation-state and that of human rights, Agamben declared the obsolescence of both.[3]

The panellists of the ‘Decolonising Human Rights’ event, however, did not support the abandonment of human rights. Instead, Walaa al-Husban, Ipek Demir, and Salman Sayyid discussed the shortcomings of the conventional concepts of human rights and suggested that decolonizing them would make them less Eurocentric, better applicable and broadly accessible.

A major critique of human rights refers, on the one hand, to the failure to fulfil the promise of universality and, on the other, the concept of universality itself. Al-Husban asserted that the claim that human rights apply to all humans by virtue of their humanity is contradicted by examples of de-humanization and the denial of basic rights in the cases of slaves, colonized people, or women. Sayyid expanded this critique pointing out that the very idea of the human is a creation of modernity which, in a decolonial perspective, is entangled with colonialism. He added that the category of the human has been classified, gendered and racialized leading to a “human of the modern” and a “human of the colonial” that reflect the distinction between the West and the non-West.

Following Demir and al-Husban, the critique that follows is twofold. The hegemonic position of Europe and its ties to the concepts of human rights and humanity not only affirm global hierarchies in which the West comes first, but they also legitimize a selective application of rights that are supposed to be universal.

The Grunwick Dispute strikers

It is the aforementioned compatibility and complicity of modernity and liberalism with colonialism and racism which Demir considers neglected in dominant narratives of human rights. Instead of acknowledging the implications of European colonialism and the contributions of non-Europeans to the development of human rights, human rights are primarily presented as an achievement of modernity and Europe. Demir challenged this Eurocentric view by calling for a recognition of the often ignored or marginalized contributions of non-European diasporas. She cited diasporic movements fighting systems of discrimination and unequal treatment such as the Bristol Bus Boycott (1963), the Imperial Typewriters Strike (1974) and the Grunwick Dispute (1976-8), which despite their significant contribution to the expansion of human rights, are mostly dismissed from dominant human rights discourses and instead reduced to claims for cultural rights. According to Demir, decolonizing has to change the way human rights are seen as an exclusively European creation.

While Demir concentrated her argument on the domestic context, al-Husban focused on the geopolitical consequences of the link between human rights, humanity, and colonialism. Departing from the premise that the humanity of parts of the world population was put into question by discourses of humanity, she highlighted how colonialism has been presented as a vehicle to bring human rights to the colonies to establish or restore the humanity of the de-humanized.

As a significant consequence of the entanglement of colonial and human rights discourses, al-Husban pointed to the emergence of two roles reflecting an established hierarchy of the West and the non-West. The role of the advocator of human rights is associated with the European colonizing subject, while the colonial uncivilized Other is accorded the role of the recipient. The advocator puts equality and protection in motion through a gesture of charity which reinforces a hierarchical relation. Seen from that perspective, Al-Husban emphasized, human rights did not liberate the colonized but rather they enhanced new forms of colonial enterprise. To decolonize human rights, she called for a rejection of European universalized definitions of rights that do not take account of local and cultural differences. Rather, human rights are to be considered a frame allowing for various interpretations in different societies.

The claim to ownership of human rights not only allows Europe to construct and maintain identities and hierarchical structures but also to regulate the “selectness of universality” (al-Husban) of human rights. This point refers to the question of who can claim and who can annul human rights. Demir and al-Husban referred to the refugee policy of the EU as examples where claims to human rights are rejected. The treatment of the so-called refugee crisis as an issue of national security rather than a humanitarian crisis has enabled states to reject refugees and void human rights. Al-Husban also highlighted the selective focus on certain groups considered to present a threat to national security, such as the focus on the supposed terrorist threat of Muslims

The panellists established that human rights are not only claimed by the West but also appropriated to mark Europe’s superiority over non-Europe. The supposed deficiency of non-Europe, in the dominant media attention, is often related to either a lack of humanity or violations of human rights, for example, in China or Saudi Arabia. This, in turn, is used by Europe to justify various global interventions, including civilizing missions that seek to impose liberal values without taking local realities into account. The panel made clear that Europe has not only claimed ownership of human rights but also the authority to set boundaries for their application and to legitimate their annulment.

Departing from the preceding critique, Sayyid questioned the project of decolonizing, if all it reveals are the colonial roots of the human rights discourse. Once the double standards and liberal premises of human rights are known, decolonizing might simply be understood as contributing to efforts to eliminate differences between humans in favour of seeing humans collectively. This might lead to nothing but reaffirming the universalizing understanding of humanity. Sayyid suggested instead that human rights should be imagined outside their modern and colonial genealogy

A condition for this exercise is to understand that there is no ultimate foundation for conceptualising human rights. This opens a space to rearticulate human rights through different kinds of vocabularies in various contexts. However, because coloniality and modernity constitute subjects, these conditions are so deeply engrained in subjects all over the world, that the biggest challenge of decolonizing lies in recognizing “the abnormity of colonial inheritance”.

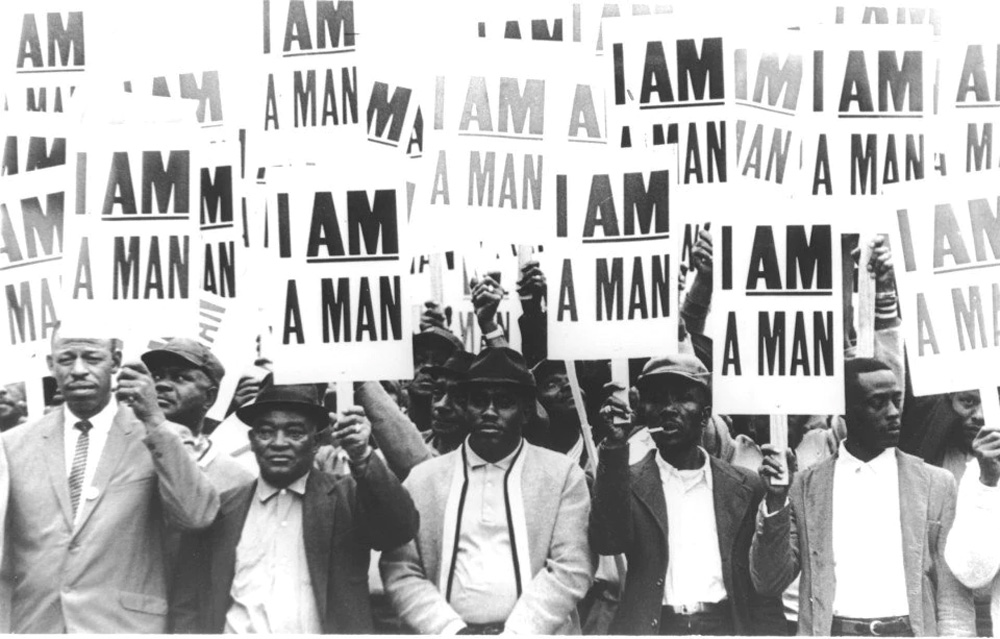

The Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike protestors holding ‘I AM A MAN’ signs (Credit)

To redress this limitation, Sayyid suggested that human rights should be thought of as “two words for justice”, as a vocabulary through which the question of justice – understood as “the matching of what is with what ought to be” – can be expressed. He recalled that human rights emerged out of fights for justice and against unfair treatment. The slogan “I am a man” in the context of Civil Rights Movements can then be read as part of a fight for justice expressed through the vocabulary of human rights.

As straightforward as this may sound, one might ask how to apply and claim human rights in the face of annulments and violations. Citing the legislation amendment in the US that legalised torture techniques such as waterboarding (as long as they did not lead to death) that were applied in places like the Guantánamo prison, Sayyid surmised that the only ammunition at hand are arguments because algorithms have not helped.

While the different contributions indicated possible paths to move forward and pragmatically use human rights, instead of declaring their end or obsolescence, a degree of reservation remains when we remember the situation of refugees in the Mediterranean or the inhumane camps in Europe and beyond. If all that is left are arguments, it remains to be asked how to state them effectively and to whom – especially from the perspective of those deprived of human rights. When thinking of successful arguments or claims for justice by the disenfranchised (and their allies), they were mostly collective, often loud, and sometimes violent. Another question concerns the implications of expressing claims to justice through the vocabulary of human rights. Could this lead to an unintended reaffirmation of the Eurocentric claim to, and universalizing understanding of, human rights? Or are the demands for justice expressed in terms of human rights by different actors in various contexts expected to subvert and eventually break Europe’s hegemony?

Credit: The Grunwick Dispute (1976-8), strikers on the picket line (https://www.striking-women.org/module/striking-out/grunwick-dispute).

Footnotes

[1] Arendt, H. 1951 [1973]. The Origins of Totalitarism. San Diego, New York, London: HBJ, pp.282-293.

[2] Ibid., chapter heading, p.267.

[3] Agamben, G. 1993 [2008]. Beyond Human Rights. Social Engineering. 15, pp.90-95, p.92.