Critical Pioneers: The Short Interviews Season – 3. Jennie Germann Molz

During June and July 2021, the Northern Notes Blog, a blog published by the School of Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Leeds is recruiting international scholars who have published an outstanding book or a collection of academic papers in the field of tourism mobilities and critical tourism analysis. By both endorsing critical theoretical scholarship and inviting innovation and critiques of critique, this summer the Northern Notes Blog invites cross and trans-disciplinary dialogue in tourism analysis.

Interviewed scholar: Jennie Germann Molz, Professor of Sociology, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, College of the Holy Cross, MA, USA (jmolz@holycross.edu).

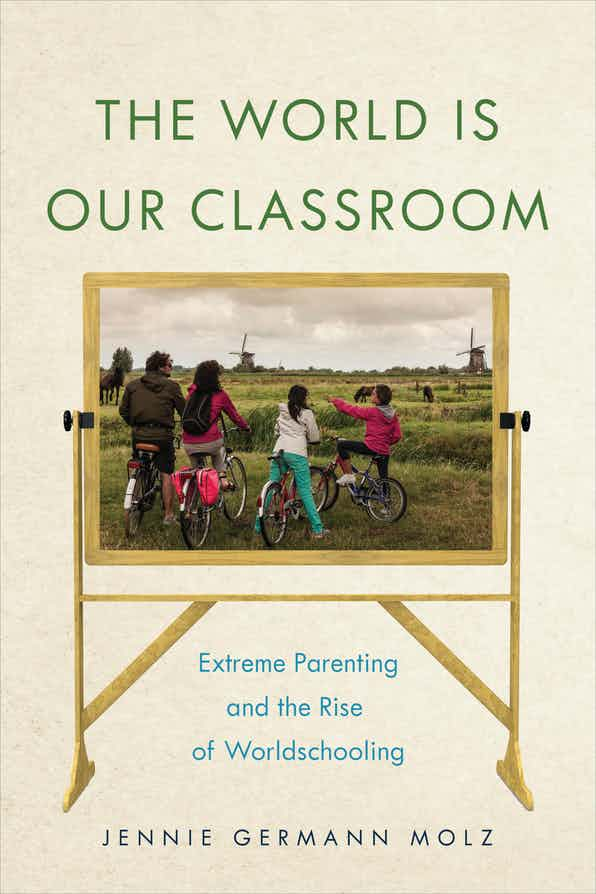

Theme of interview: The World Is Our Classroom: Extreme Parenting and the Rise of Worldschooling, New York: NYU Press, 2021.

This book explores a new alternative lifestyle movement called “worldschooling” that has emerged over the past decade or so as middle-class families from the Global North choose to take their children out of conventional schooling and educate them while traveling the world. The book describes the way worldschoolers “do family” on the move and examines how these parents deploy mobility as a strategy for preparing children to thrive in a diverse world and uncertain future.

What is the central argument in your book?

The World is Our Classroom: Extreme Parenting and the Rise of Worldschooling is an ethnographic study of parents who educate their young children while traveling the world. Adopted primarily by white, middle-class parents from the Global North, worldschooling represents a new kind of life strategy that melds tourism, educational, and work mobilities. At first glance, worldschooling appears to be a countercultural practice, but I argue that it is actually emblematic of the mobile lifestyles that are becoming more common in contemporary society as individuals search for the “good life” through new configurations of embodied, material, and mediated mobility.

When I started this research, my intention was to better understand how worldschoolers were performing family life on the move. Despite the fact that families have been on the move throughout history, western imaginaries of family life have tended to settle on localized symbols like the hearth and home. I was curious to know how worldschoolers were “doing family” on the road with their kids and what had prompted them to abandon suburban homes, conventional schools, and stable careers to do so. This soon led to the discovery that, like so many other families around the world and throughout history, worldschoolers were traveling in search of the “good life.” They saw mobility as delivering everything they imagined the good life to be: an opportunity to spend quality time together, a way to develop their children into adaptable global citizens, an escape from the social pressure to consume and conform, and a chance to live life deliberately rather than settling for the status quo.

I also came to understand that their vision of the good life was intertwined with the sense of uncertainty that characterizes late modernity. These families were coping with the effects of serial financial crises and hollowed out social programs, competitive university admissions and scarce early-career options, the rise of free-lance and gig-economy work, and waning trust in government institutions like public education. This made for an uncertain landscape that was both exhilarating and terrifying. Late modernity’s double-edge sword of freedom and anxiety was evident in parents’ stories about quitting their jobs rather than enduring inevitable corporate layoffs or pulling their kids out of schools that were failing to equip them with 21st-century skills.

In the book, I argue that worldschooling families adopt a lifestyle of extreme mobility as a way of harnessing these uncertainties rather than falling victim to them. The book details the embodied practices and the emotional strategies these families deploy in order to live, and live well, with insecurity and risk. I describe how worldschooling parents seek to “future-proof” their children for a changing world by equipping them with new forms of social, emotional, and cultural capital derived through travel.

What is, in your opinion, your work’s most important contribution to tourism studies? How does it relate to the theme of this interview?

Whereas my previous two books, Travel Connections (Routledge) and Disruptive Tourism and its Untidy Guests (Palgrave Macmillan), were situated squarely within tourism studies, The World is Our Classroom comes at the topic from a slightly different theoretical angle. Worldschooling as a practice, and my analysis of it, trouble the categorical boundaries between tourism and migration, nomadism and family life, and work and leisure. My starting point here is not tourism mobilities, necessarily, but rather a mobile lifestyle that integrates leisure travel with education, work, and the everyday routines of family life.

In this sense, we might consider worldschooling as an example of what Jonas Larsen (2006) calls the “de-exoticization of tourist travel.” Larsen questions the assumption that tourism is primarily about experiencing the extraordinary or exotic elsewhere in contrast to the everyday-ness of home geographies. Instead, he points to examples of tourists traveling together with their families or to visit friends and relatives in other places, in which case tourism is more about the reproduction of familiar social relations than an escape from social obligations. Worldschoolers do see themselves as escaping from the status-quo of suburban life, but life on the road is still composed of daily responsibilities related to living, learning, and working on the move.

These families participate in activities we might label as tourism, such as going to the beach, camping, hiking, visiting heritage sites and museums, trying local foods, attending cultural events, and taking photographs, to name a few, but because these activities are also framed as educational experiences or combined with mundane chores like doing laundry or used as content for income-generating lifestyle blogs, it is hard to separate them from the other tasks of daily life.

And it is not just that worldschoolers combine leisure pursuits with these everyday activities that makes it so difficult to carve out tourism as a separate object of analysis. The viability of a mobile lifestyle like worldschooling relies on tourism infrastructures and technologies which are, in turn, entangled with postcolonial geopolitics, global wealth inequalities, and neoliberal capitalism. Worldschooling illustrates the fact that tourism is not ancillary to but interwoven with these processes.

What vision of criticality do you uphold in the published title? Does your showcase work belong to a school of thought or a paradigm and why/how?

The World is Our Classroom is situated within the field of mobilities studies and engages with the critical perspective advanced by the mobilities paradigm. The mobilities paradigm has always been concerned with questions of power, access, and inequality. It also pushes us to expand our focus beyond the divide between who travels and who stays put to examine the differential conditions of mobility and immobility more broadly. What becomes apparent in my analysis is that even if the families in my study have limited economic resources, they are flush with other forms of capital: cultural, social, network, mobility, and cosmopolitan capital, for example. This means that, unlike some other mobile families, worldschoolers are able to narrate their mobility as valid and valuable and can move around the world with an ease and peace of mind others don’t necessarily enjoy.

Zygmunt Bauman’s distinction between “tourists” and vagabonds” is useful for thinking about these inequalities. As Bauman puts it, tourists are the “choosers” in a consumer world where “their degree of mobility – their freedom to choose where to be” sets them apart from vagabonds who are either stuck in place or thrown out from their homes against their will (1998, p. 86). According to Bauman, tourists “travel through life by their heart’s desire and pick and choose their destinations according to the joys they offer” (p. 86). The worldschoolers in my study would certainly land on the “tourist” side of Bauman’s chart. They take choice to an extreme. To hear them describe it, theirs is a lifestyle designed by choice. They see their children’s schooling as a choice, the kind of work they do as a choice, and the style of parenting they adopt, the communities they join, and the kind of citizenship they practice all as a matter of choice.

Even so, Bauman tempers this freedom with the reminder that “all of us are doomed to the life of choices” (p. 86). Worldschooling families may be on the privileged end of the spectrum Bauman describes, but they are also subject to the tragic effects of late capitalism. Even as they parlay their mobility into new forms of value for themselves and their children, they are simultaneously navigating new forms of vulnerability to state and economic regimes that require unflinching self-sufficiency.

It might be tempting to dismiss these families’ life strategies as selfish overconsumption by the global elite, but I try to offer a more nuanced picture of the way privilege and precarity are intertwoven in these families’ stories. In an effort to move beyond a dichotomy of the mobility “haves” and “have-nots,” I draw on Mimi Sheller’s work on “mobility justice” to make a case for what a more just and collective “good mobile life” might look like.

Is there an area in tourism scholarship that remains underdeveloped? Do you believe that you may have a role in its development?

I expect that coming to terms with the pandemic’s ongoing impacts on tourism mobilities will occupy the field for quite some time. As we know, tourism has always been at the center of some of the most urgent social, political, and environmental problems the world faces today, a point the pandemic highlighted quite starkly. When the threat of the COVID-19 virus first slowed and then halted travel and tourism mobilities in the spring of 2020, tourism scholars amplified the alarm bells they had been ringing for years about overtourism, environmental degradation, growing social inequalities, and the need to decolonize tourism. They saw the disruption as a moment to rethink the unsustainable path we were on and perhaps take a different direction altogether. Has the pandemic crystallized the will to shift into different modes of tourism? Or will the impulse to get back to normal – and even make up for lost time – overpower good intentions? In the past few days, protests against the return of massive cruise ships to Venice erupted along the Giudecca Canal, but the ship was carrying more than a thousand willing passengers. What will these unfolding pandemic scenarios tell us about the conditions under which real change is possible?

In my research, I am interested in continuing to trace the intersections between tourism mobilities and mobile lifestyles through the new arrangements of remote work and schooling the pandemic made possible. For a certain class of workers and students who have proven themselves to be suitably productive outside of the cubicle or the classroom, the feasibility of working and learning from home – which many interpret as anywhere – may promote even more, not less, mobility. We are already seeing trends toward relocation and location independence as people move to more rural destinations. These so-called “zoom towns” have seen an influx of remote workers who can afford lower property costs and enjoy a slower pace of life close to nature and leisure amenities. Like digital nomadism and vandwelling prior to the pandemic, these untethered lifestyles seem to be a way of coping, not just with a pandemic crisis, but with the social and economic uncertainties of neoliberal capitalism. I am curious to understand how tourism – as an industry, an infrastructure, and an imaginary – plays into these survival strategies.