A Trump Inclusive: Reading Nabokov in the Age of COVID-19

Written by Dr Sarah Marusek

Dr Sarah Marusek questions the universal norms on which 'evidence-based science' rests in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As the COVID-19 crisis further colonises our socio-political landscapes, I keep hearing public voices call upon politicians to better craft policy according to evidence-based science. It seems that we not only want to take control of the virus, but also its socio-political impacts. After hearing this call again and again, I started to think of Hermann Karlovich. While at first the thought made me laugh, out loud, soon my impulse was to shudder. My fear is that we are still living in the chasm between modernity and post-modernity. There is evidence of both and neither; there is nothing certain anymore except our uncertainty.

I first encountered Hermann as a precocious young reader who avidly devoured nineteenth and twentieth century literature, particularly that of the Russian variety, perhaps seeking to shed light upon the many unanswered questions about my paternal grandfather’s secret Russian past. Vladmir Nabokov’s paradoxical mastery of language, in particular, allowed me to chew over every single page, almost in a rapture. I first tasted Lolita as a teenager and then Pnin as a student of literature and I loved both so much that I soon dug into to Nabokov’s wider catalogue, including his autobiography Speak Memory and lesser known Russian works, such as Despair, the novel in which we meet dear Hermann.

A distinctly postmodern affair, the plot of Despair is as follows: Hermann is a Russian manufacturer of chocolate who is both bored and deranged (Nabokov wonders if anybody will call him ‘the father of existentialism’). While away on a business trip, Hermann encounters a homeless man named Felix and convinces himself that he is his doppelgänger. Meanwhile, Hermann’s wife conducts an affair with her cousin under his own nose, but he refuses to see. Slowly, it becomes increasingly obvious that Hermann is descending into madness. But the reader cannot stop him. Ultimately, he concocts a plan, what he calls a work of art—even a masterpiece—that results in the murder of Felix, who is disguised as Hermann in order to collect on his life insurance policy. But, of course, Felix bears no real semblance to Hermann, and so his capture by police is imminent as the novel ends.

Despair is a parody, both generally of life and particularly of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel The Double, which is referenced by Hermann. What I loved most about the plot is that even though it is absolutely silly, and Hermann is decidedly unlikeable, the story is also somehow perfectly seductive. And breathlessly so. I remember—about the same time that I was reading it—being at university as an incoming freshman. Throughout my first year, a number of people excitedly told me that I had my own doppelgänger in Williamsburg, Virginia. An outgoing senior who was studying abroad, or somebody who had already graduated, I cannot remember which. I was so intrigued, even proud, that I romanticised our connection. This was until I finally met her and felt utterly betrayed (okay, this was long before the advent of Facebook), because this infamous stranger looked nothing like me (or so I insisted to myself). It was a bit heart breaking, that evidence-based, but visceral, reaction. Nevertheless, her friends and comrades continued to stop me throughout my sophomore year, to tell me all about my doppelgänger. The two truths coexisted.

The collapse of Eurocentrism as the only Truth in town, with its accompanying universalism, creates even more possibilities of coexistence, and yet social scientists continue to struggle with evidence-based science. Not only do we disagree about what counts as scientific evidence, but we also learn to interpret it in completely different ways. One scientist’s externality is another scientist’s reason to believe that our planet’s existence is in jeopardy. And even when we do agree that climate change is altering our planet in fundamental ways, we still cannot agree to change anything, including the dynamic of man versus nature.

Even though COVID-19 is probably both man-made and completely natural—this is true for both the virus and its socio-political impacts—we still choose to ignore yet another sign that man versus nature is probably not a very helpful binary here, indeed it is one of the many unhelpful binaries that Eurocentrism has tried to enshrine as real, despite being a concept that is historically contingent, and even then not entirely or always helpful.

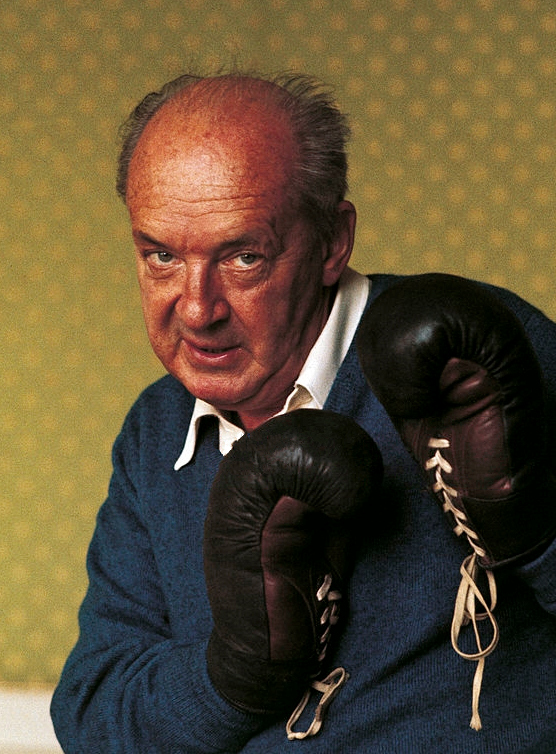

Today, in the age of the Anthropocene and the internet, seeing is no longer believing, as ‘the deep fake’ now warns us, even though the evidence is all around us. Like Hermann, we can no longer trust what we see. I mean, I still cannot tell without a shadow of a doubt that this baby is not President Donald Trump’s doppelgänger? It is so uncanny!

But in all honesty, although the American presidency is now a laughingstock in the age of COVID-19, any claims that Trump is the worst US president are still deeply disingenuous. Americans have long been ruled by liars, misogynists, adulterers, racists (including slave owners) and mass murderers (the atomic bombs were only the beginning).[i] Trump is merely the first to be orange. The evidence is there if we want to see it, but that takes a level of humility that our fantasy of man versus nature has long eviscerated.

Interestingly, in the preface to his 1966 translation of the novel, Nabokov admits that there are now three different versions of Despair: the Russian original, his first English translation, and the revised Russian original and his second English translation. Some will cry out, but which edition is the most authentic? Others will vexedly murmur, this merely illustrates how nothing is authentic! Meanwhile, we are all probably forgetting to celebrate the fact that there are now three different versions of the same masterpiece, a triumvirate that we can respectively feast upon in many ways, finding its alternate meanings, disagreeing about its potential merits or faults, all something very natural, and universally human.

Dr Sarah Marusek is Research Fellow, at the School of Sociology and Social Policy and member of the Editorial Board, Northern Notes Blog.

Work cited:

Nabokov, Vladimir. 1989. Despair. New York: First Vintage International Edition.

[i] If former President Barack Obama apologised for just one civilian death each day, it would take him three years to account for those killed by drones during his presidency.

Author

Dr Sarah Marusek

Research Fellow